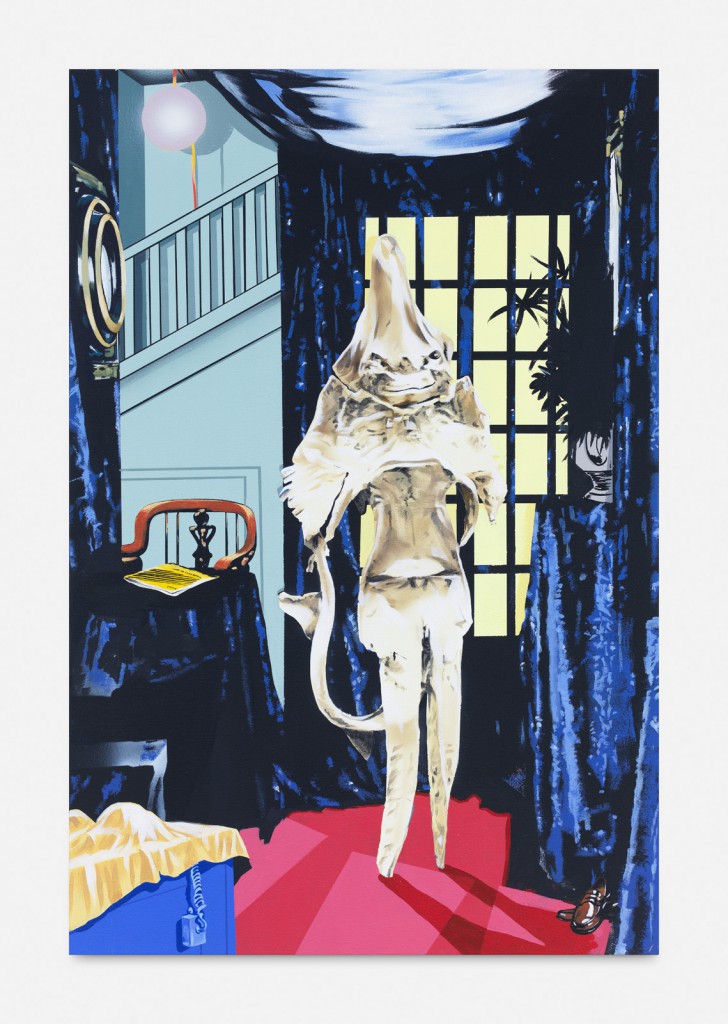

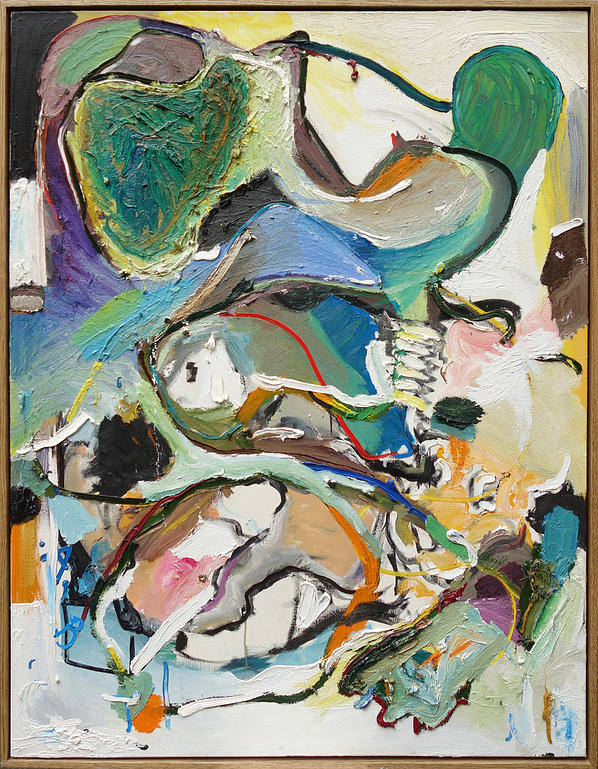

Jamian Juliano-Villani, Penny’s Change, 2015,

What makes a painter paint? In her Bedford-Stuyvesant studio, artist Jamian Juliano-Villani uses a digital projector to create surreal paintings and discusses the graphic source material that inspires her. Juliano-Villani’s Brooklyn studio is crowded with a wildly varied collection of books ranging from 70s-era fashion, to commercial illustration, to Scientific American-style photography, to obscure European comic art. This vast image bank—which the artist began collecting in high school—generates the building blocks for her mashup creative process. “When I’m working I’ll have thirty images in a month or two months that I’ll keep on coming back to, and I’ll try and make those work with what I’m doing, but they’ll never look like they’re supposed to be together,” says Juliano-Villani. “That’s when the painting can change from an image-based narrative to something else.”

Working quickly and intuitively with the projector, Juliano-Villani toggles through a series of potential images on her laptop as a way to discover solutions for content and composition. Long attracted to cartoons, the artist borrows from illustration as a way to deflate painting’s historical pretensions and to speak in a more direct language; and yet, despite her use of vernacular imagery, what her works ultimately communicate might only be personally understood. “Painting is the thing that validates me and the thing that makes me feel good. I care about it, and they care about me. That’s why I put the things that I collect and really, really love in my paintings,” says Juliano-Villani. “They’re helping me figure out the things that I can’t communicate to myself yet.”

Her trippy acrylic paintings combine cartoonish imagery from far-flung sources, some of them actual cartoons from artists like Chuck Jones. She calls her use of other artists’ work “simultaneous exploitation and homage.”

Juliano-Villani explained her thinking in a Facebook comment: “It’s important to realize that all visual culture is fair game for artistic content, ‘appropriation’ isn’t a ‘kind’ of work, it’s almost all art. When making a painting or a print or a sculpture, it’s nearly impossible to make something without thinking of something else. A good reminder that when dealing with images 1) once an image is used, it isn’t dead. it can be recontextualized, redistributed, reimagined. 2) It should have several lives and exist in different scenarios.”