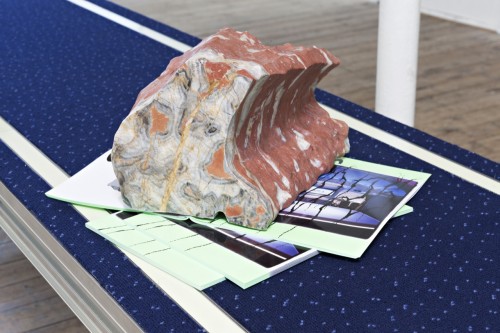

Yngve Holen, Extended Operations, 2013, Sensitive to Detergent, Tired, 2011 and Hater Headlight, 2015

Emerging from the 3D-printed rubble of Berlin’s “post-Internet” art scene, the Norwegian artist Yngve Holen is a cold empiricist and a slapstick comedian. With sculptural test-subjects ranging from minor appliances (tea kettles and washing machines) to high-industrial behemoths (commercial airliners and CT scanners), his works map the anatomical features of a new human-machine eco-system.

René Descartes (1596–1650) had a problem with animals. Or, rather, he had an animal problem. In the Meditations, the “father of modern philosophy” used skepticism to arrive at a radical theory of mind-body dualism. Bodies were machines. Minds were souls. But since the theological doctrines of the time stated that humans were the only animal that could have a soul, it was imperative for Descartes to prove that animals did not have minds either. The French philosopher thus responded by cutting animals open in private and writing about it in public. He penned a number of letters and texts that described animals as deceivingly complicated machines. What appeared to us as signs of their consciousness – their human-like qualities, or their screams under the knife of live dissection – were in fact spring-loaded responses to external stimuli. In the 21st century context, Descartes’s “animals are robots” writings have become the most unpopular of his theories. Perhaps it is because society as a whole has grown to have more empathy towards animals. Or perhaps it is because we know more about machines. Cutting something open to check for its soul seems like lunatic behavior now. At the very least, those of us in this century would use an ultrasound machine first.

In 2011, the artist Yngve Holen (1982–) ran over a chicken with a Toyota RAV4 and 3D-printed its remains. Unlike Descartes’s test subjects, Holen’s chicken was already dead, plucked, and de-clawed. Yet, when he crushed it open, a soul appeared:

Initially, I wanted to scan road kill. But it was difficult to find, and you can’t laser-scan fur. So I got the idea that I’d go to the supermarket and buy a chicken, so I could run it over and scan it. The meat we see in stores is almost a type of design object. For example, a chicken at a supermarket is so far from being a chicken. It’s had its feathers taken out. It’s cut into thighs and wings and drumsticks with lasers at some factory. It undergoes all these sculptural changes in order to transform from chicken to “poultry.” It’s a scary industry. If you don’t buy bio, chicken is cheap as hell. For an artist, it’s cheaper than buying clay. Then, when you drive over it and crush those bones – when you turn it into road kill – it’s suddenly this individual thing again. You give the chicken a soul by running it over. And then you extract that soul by scanning it.

With the artist-publication ETOPS, Holen formed an editorial extension to his sculptural practice. Comprised of long-form interviews with specialists from a variety of occupations, the magazine performs verbal dissection on the routines of otherwise opaque industries. It proffers details that simultaneously augment and drain the fear surrounding professions that operate in the intersections of body and machine. Aptly, the first ETOPS investigated the experience of air travel. In addition to an interview with a commercial pilot, the publication featured camera phone pictures of cruising-altitude sunsets and rows filled with cramped legs.

ETOPS is regulation system in aviation that says how many minutes you can fly a twin-engine aircraft without being in a certain radius of an airport. So a plane will be certified for, say, 120 minutes. Or now some are certified for 720 minutes, so you can basically fly wherever you want. But there’s this pilot joke that ETOPS stands for “Engines Turn, or Passengers Swim.” It’s funny. Metaphorically, it’s a question about how long we can stretch an idea before we crash it. How long are you allowed to spin off certain ideas before it doesn’t fly? The materials can only go for a certain amount of time. After that, the idea can go further, but the materials then won’t allow for it. We tend to think that these thresholds don’t exist, because they keep getting pushed further and further. Like, how far can the body swim before it drowns? We want to know that limit.

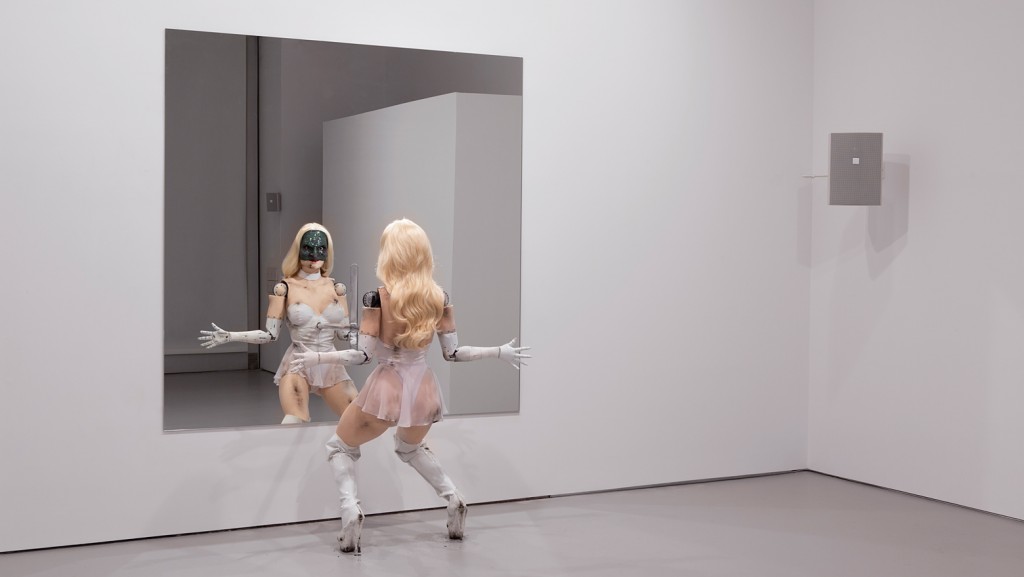

With ETOPS, Holen turns his line of inquiry away from the insides of machines and towards the invisible limits of how far the body can be stretched into something foreign from itself. For the second edition of ETOPS, designed by Per Törnberg, Holen and his editorial partner Matthew Evans travelled to Los Angeles and Monte Carlo to interview members of the pornography and plastic surgery industries. The resulting collection of anonymous interviews provides a look into two fields of practice that blur the distinctions between the natural and the artificial. By discussing the minutia of these occupations, ETOPS provides a textured account of everyday life in a futuristic present. During a dinner conversation, a pornstar gives advice on what to eat before sex scenes. In another interview, a plastic surgeon discusses how the placement of scars has been effected by trend cycles; The aesthetic has changed through the years. What is good-looking now may not have been 10 years ago.

For his solo exhibition “World of Hope” (2015) at Galerie Neu in Berlin, Holen released the second edition of ETOPS alongside a series of works make from the faces of CT scanners, which the artist dressed in custom-fitted fishnet fabric. Unlike the dissected water vessels of Parasaggital Brain, the sculptures allude to the possibility of seeing inside without incision. They present a technology designed to see through skin that is encased inside a fabric designed to see through clothing. Mounted on the wall as a type of relief, the works masquerade as paintings, winking at the Renaissance ideal that a picture should be a “window” into another world. They allude to the limits of the two-dimensional – the blurry and flattened organs that appear in radiology. Their shape suggests a type of industrially-designed orifice, although it is unsure whether it is designed for entrance or exit.

Source: Kunstkritikk.

Text: Thom Bettridge, 032c.

All images belongs to the respective artist and management.