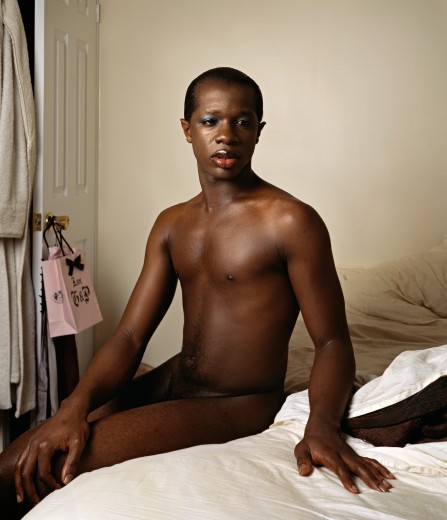

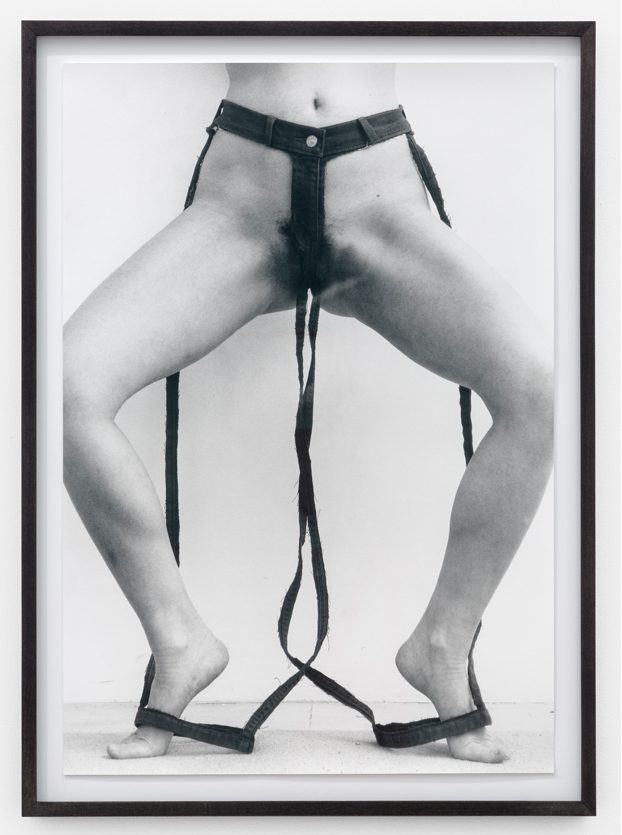

Haim Steinbach, Display #31G — An Offering: Collectibles of Ellen and Michael Ringier, Kunsthalle Zurich, 2014

Producing an extraordinary body of work throughout his impressive forty year career, Haim Steinbach has redefined the status of the object in art through his continued investigation into what constitutes art objects and the ways in which they are displayed.

When I began working with objects in the late 1970s, most objects I employed were used objects that I got from flea markets and yard sales. For instance, all the objects in an installation I did at Fashion Moda in the South Bronx in 1980 came from the neighborhood second-hand stores or were picked off the street. The idea of a desire for a “cultural object-as-commodity,” something which “exists outside,” intrigues me because I believe that what exists outside eventually comes inside. A “commodity object,” once acquired, becomes internalized.

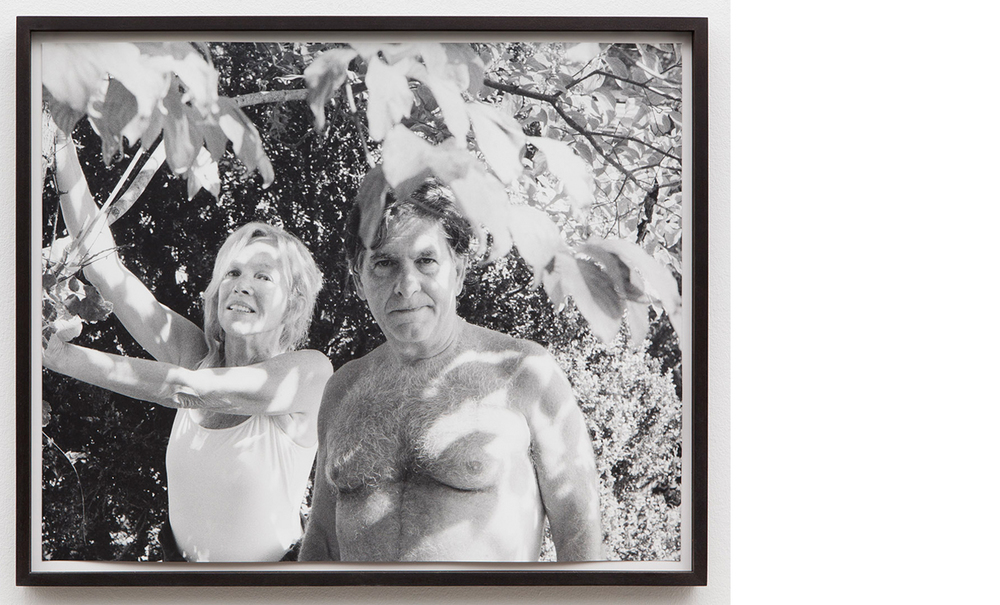

Through juxtaposing paintings, sculptures, artefacts and children’s playthings, Steinbach uncovered alternative meanings inherent in the objects, while subverting traditional notions of display and the value of objects. In presenting these loans and the salt and pepper shakers, Steinbach also unites the day-to-day habits of the home with the seemingly more conventional museum-based act of collection and display.

Up until the mid-1970s, Steinbach explored Minimalist ideas through the calculated placement of coloured bars around monochrome squares. He then abandoned painting to configure works using linoleum based on a range of historical floor designs, responding to both high and low cultural narratives. By the late 1970s, Steinbach began a transition to the three dimensional, collecting and arranging old and new, handmade and mass-produced objects, coming from a spectrum of contexts. These objects were displayed on what Steinbach termed “framing devices”, ranging from simple wedge-shaped shelves, to handmade constructions, to modular building systems.

Steinbach’s preoccupation with the fundamental human practice of acquiring and arranging objects has remained a key focus within his work and brings to the fore the universality of this common ritual.

“People seem to build their own cathedral inside their house. They select the objects that they like to live with, and they make a shell for themselves. They cultivate their little domain. In terms of my own experience with objects, there was a time when I went through a purist period. I didn’t want to have anything in my house — it was simpler just to have very few things around. I went through an evolution in my own work from a minimal, reductive language based on the conceptual activity of the late 1960s and early 1970s, toward a point at which a whole other range of discussions began to emerge. I realized that I had developed an incredible bias toward objects, probably as a result of a resistance to an ideology of “commodity fetishism.”“

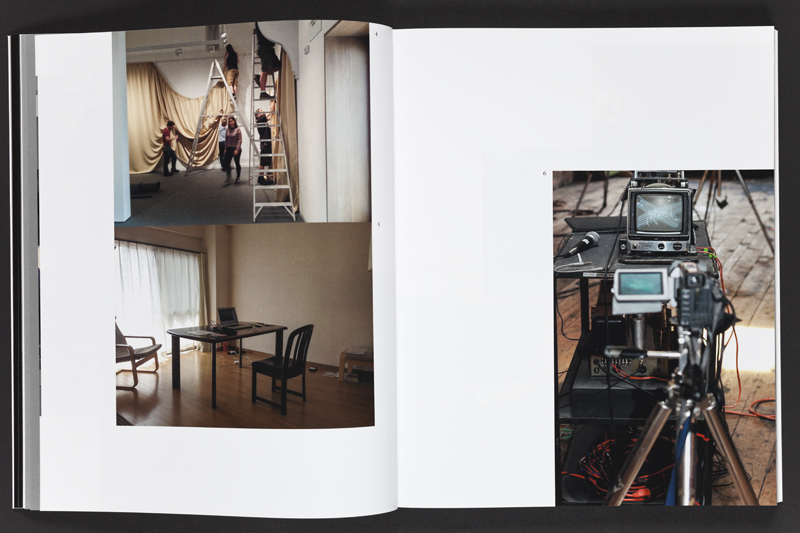

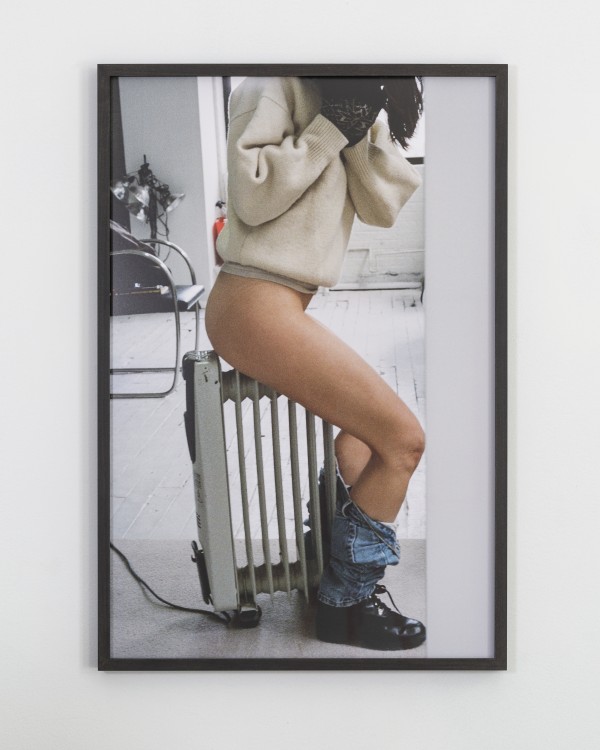

Steinbach’s interest in display extends to the environments in which objects are placed, and thus photographs, images, models and recreations of interiors are prevalent throughout the exhibition. He often positions his objects within larger architectural installations resembling domestic interiors. Several of these historical installations have been reconceived within the exhibition, where sheets of wallpaper sit on studded walls. These walls serve to guide the viewers’ navigation through the galleries and highlight the architectural qualities of the space.

On show within the installation was a new installation, comprising salt and pepper shakers lent by members of the public. By transporting objects that hold their own stories into the Serpentine Gallery, Steinbach’s participatory gesture reactivates them within this new context and makes the connection between the private and the public sphere.

“Objects, commodity products, or art works have functions for us that are not unlike words, language. We invented them for our own use and we communicate through them, thereby getting onto self-realization.”

Text:Joshua Decter, Journal of Contemporary Art http://www.jca-online.com/steinbach.html and Press Release, The Serpentine Gallery, http://www.serpentinegalleries.org/exhibitions-events/haim-steinbach-once-again-world-flat.

Artist Website: Haim Steinbach, http://www.haimsteinbach.net.

All images belongs to the respective artist and management.