Author Archives: Magazine Contemporary Culture

Charles Harlan, Sculpture

Charles Harlan, Stack, 2015, Roll Gates, 2012 and Counter, 2013

Drawing inspiration from Land Art of the 1970s, Harlan avails himself of the most common materials at hand – including such hardware store staples as ladders, shipping palettes, and one-ton metal pipe – in his large industrial works. Huge in scale, Minimalist in form, and shown both indoors and out, Harlan’s art has often been referred to as Duchampian in its reliance upon readymade components, its deceptive simplicity, and it spatial humor. His stacking and layering of recognizable, utilitarian materials renders surprisingly potent forms that invite unexpected associations.

Charles Harlan sculpture and work invites contemplation of the ways in which we adapt to and absorb the toughness of the urban landscape. Pristine, immutable walls are made from the same sheet metal fencing that encloses myriad outdoor parking lots and construction sites, and hosts graffiti and flurries of advertisements throughout the cityscape. But whereas the world around us is wild and feral, Harlan’s work is carefully ordered, throwing into higher contrast the realms of tumult inside.

Harlan was raised in Smyrna, Georgia, and his work exhibits a vernacular, domestic flair, as if the suburban housing tracts featured in Dan Graham’s Homes for America (1966) were taken apart and repurposed as elegant, redneck Minimalism. With Shingles (2011), for example, Carl Andre’s floor-based metal works meet their working-class counterpart, as copper plates are exchanged for patterns of overlapping asphalt roofing tiles; Siding (2011), meanwhile, replaces Donald Judd’s shiny metal cubes with the work’s namesake – and very plebeian – exterior vinyl wallcovering found on many a tract house; and by simply lifting a marble countertop off the bathroom sink and onto the wall, Counter (2012) proves that even the slightest of gestures, such as a change of orientation and context, can render foreign something familiar – the everyday as convincing art object. Similarly, with Pipe, it’s as if one of Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1976) was transported from the desert to this small, white cube gallery on the Lower East Side.

Equally industrial as Holt’s work, though perhaps more refined-looking with its clean metal surface and, when struck, resonant timbre, Harlan’s invasive culvert more closely pressures the thin distinction between rote object and institutionally legitimated artwork. Even if they’re in the middle of nowhere, Holt’s tunnels are art because the artist presents them as such; Pipe is equally authored and institutionalised. That it’s a pipe is precisely the point. While it’s a beautiful object, it illustrates how arbitrary ‘art’ really is. The term may designate anything, from a painting to a pickle in a jar. The latter, displayed in the gallery’s back office, is sold by Harlan’s mother in her hardware store; it could be an artwork too, if he willed it.

Arab Contemporary Art: Artist Collective GCC

GCC, Exhibition View, Royal Mirage, 2014, Chartered Cruise, Rolls Royce Silver Phantom, sound, ephemeral/performance, 2013, and Royal Mirage III, 2014

The artist collective GCC has been making arab contemporary art that is both inspired by and addresses the contemporary culture of the Arab Gulf region. Consisting of a “delegation” of nine artists, the GCC makes reference to the English abbreviation of the Gulf Cooperation Council, an economic and political consortium of Arabian Gulf nations. Founded in the VIP lounge of Art Dubai in 2013, the GCC makes use of ministerial language and celebratory rituals associated with the Gulf. The collective consists of Nanu Al-Hamad, Khalid al Gharaballi, Abdullah Al-Mutairi, Fatima Al Qadiri, Monira Al Qadiri, Aziz Al Qatami, Barrak Alzaid, Amal Khalaf.

For their inaugural series of exhibitions, the collective focused on the notion of achievement, focusing on the rituals that mark accomplishment as well as the physical objects that embody them. They have created a series of Congratulants based on trophies exchanged in the Gulf as well as videos examining ribbon-cutting ceremonies and installations that reference the spectacular cities that have been recently constructed in the region. The GCC’s visual language is not one of irony or hyperbole, but rather a way of framing culture that reveals the ambiguity and nuance of how people live today.By utilizing new mediums like HD and 4K video, in addition to appropriating traditional forms like news radio and miniature model building, the GCC span a range of artistic practices. They are rooted in the legacy of identity politics while engaging with new ways of relating images and objects. With members trained in architecture, design, music, and of course art, the collective embraces an interdisciplinary way of working that produces arab contemporary art that are both coherent and concise in their concept and execution. They make use of visuals that are largely known to the late-capitalist consumer—advertising and brand management that is employed by global business and nations alike.

Upon entering Achievements in Swiss Summit, London’s first GCC exhibition at Project Native Informant, it becomes immediately apparent that the luxurious setting is apt – the Rolls Royce hovering by the entrance on the opening night is not a mode of transportation for an ostentatious Frieze-goer but a prop that plays an integral part of the show’s concept. Achievements in Swiss Summit acts as a formal celebration of the artistic union of the GCC collective, an auspicious event that reinforces its first meeting in Morschach, Switzerland and announces through speakers in controlled, mellow tones its intentions as a High Level Strategic Dialogue.

Dance: Xavier Le Roy, Nudity Has Been Around From Prehistoric Times

Xavier Le Roy and Eszter Salamon, Gisxelle, 2001

For Le Roy, nakedness is not a shock tactic but a quest for the sculptural and the sublime. “Nudity has been around from prehistoric times,” says John Kaldor. From 35,000-year-old figurines of Venus to the pursuit of male bodily perfection in Greek and Roman marble statues, Temporary Title is following a long artistic tradition. “Everybody is the same but is different,” says Le Roy, “The skin is great at showing that.”

For two decades, Le Roy has been tearing contemporary dance away from its conventional home in the theatre and placing it firmly into the art museum (appearing everywhere from London’s Tate Modern to the Museum of Modern Art in New York). His work is an “exhibition”, a moving landscape if you will, a space where visitors can stroll in and out as they see fit, spending 10 minutes or six hours consuming the art.

Xavier Le Roy holds a doctorate in molecular biology from the University of Montpellier, France, and has worked as a dancer and choreographer since 1991. He has performed with diverse companies and choreographers and produces his work since 1994.

His most famous composition to date, Self Unfinished (1988), sees Le Roy use an elasticated black jumper and trousers to divulge, and then cover up, parts of his body, before peeling off his clothes altogether. In the process he becomes barely human. He is a robot, a raw plucked chicken carcass, a series of shapes and curves, his anatomy a ball of clay to mould.

When he performs Self Unfinished around the world, he is still struck by the “density of concentration” between himself and viewers, so thick it’s “like you can almost touch it”, he murmurs, rubbing his fingers together. Le Roy’s art is in his audience’s hands too (hence the open rehearsals and feedback sessions). He recalls one onlooker who was asked a question in a practice run of Temporary Title. Faced with the nakedness, he answered honestly, later telling the artist he could no longer “dress up” his answer.

But if being nude is being vulnerable, so, ironically, is putting back on clothes. Temporary Title’s performers work in shifts, dressing and undressing in front of the watchful eyes of the crowd. In the process they become “coloured in”, observes Christopher Quyen. Clothes act as identity: a conscious, carefully chosen image.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans, Young Man, Jeddah, A, 2012, Nite Queen, 2013 and Young Man, Jeddah, B, 2012

The German artist Wolfgang Tillmans is the recipient of the 2015 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography. On December 1, 2015 an exhibition of Tillmans’ work opened at the Hasselblad Center, Sweden. On the same day, the Hasselblad Foundation hosted a symposium with the award winner, and a new book by Tillmans was released.

Wolfgang Tilmans was born in Remscheid, Germany in 1968, and is a worldrenowned artist who has redefined the popular understanding of photography as a gallery-based medium. He studied at Bournemouth and Poole College of Art and Design in Bournemouth, Great Britain from 1990 to 1992 and mostly lived and worked in London for much of the 1990s until the mid 2000s. He was officially recognized in the year 2000, when he won the prestigious Turner Prize in London, and it is a testament to the groundbreaking nature of his work that to this date he remains the only artist working primarily with photography to have been awarded this accolade. His work is in the collections of museums all over the world, including key institutions in The United States, The United Kingdom, France and Germany. He has exhibited widely and constantly since the late 1990s and has recently had large-scale exhibitions at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Kunsthalle Zurich, K21, Dusseldorf, Museo de Arte de Lima, Peru, and Museo de Artes Visuales, Santiago, Chile. In 2014 installations by Wolfgang Tillmans were shown as part of the 8th Berlin Biennale, Manifesta 10 and in collection displays at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Recently Wolfgang Tillmans was also acclaimed for his highly original contribution to the Venice Architectural Biennale; a stunning two-channel video installation of his own photographic investigation of urban landscape in the age of globalization, which is presently displayed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Tillmans currently lives and works in Berlin and London.

Tillmans’ work is characterized by an extremely diverse and restless attitude to his subjects. His work ranges in focus and approach from street photography and urban portraiture (including important considerations of subcultures, queer politics and the AIDS crisis) to travel, landscape, still life, pictures of the sky and pure abstraction. Moreover, as well as producing iconic images, Tillmans is doubly significant in the breadth of his interests and approaches for the way in which he successfully demolishes the borders between apparently contradictory practices. In recent years, he has produced substantial and significant bodies of purely abstract photographic work, experimenting both with chemical and technical means, while maintaining a curiosity for the continued potential of more documentary images. For his most recent body of work Neue Welt (New World) Tillmans traveled throughout the world exploring it in a deviation from his beaten path.

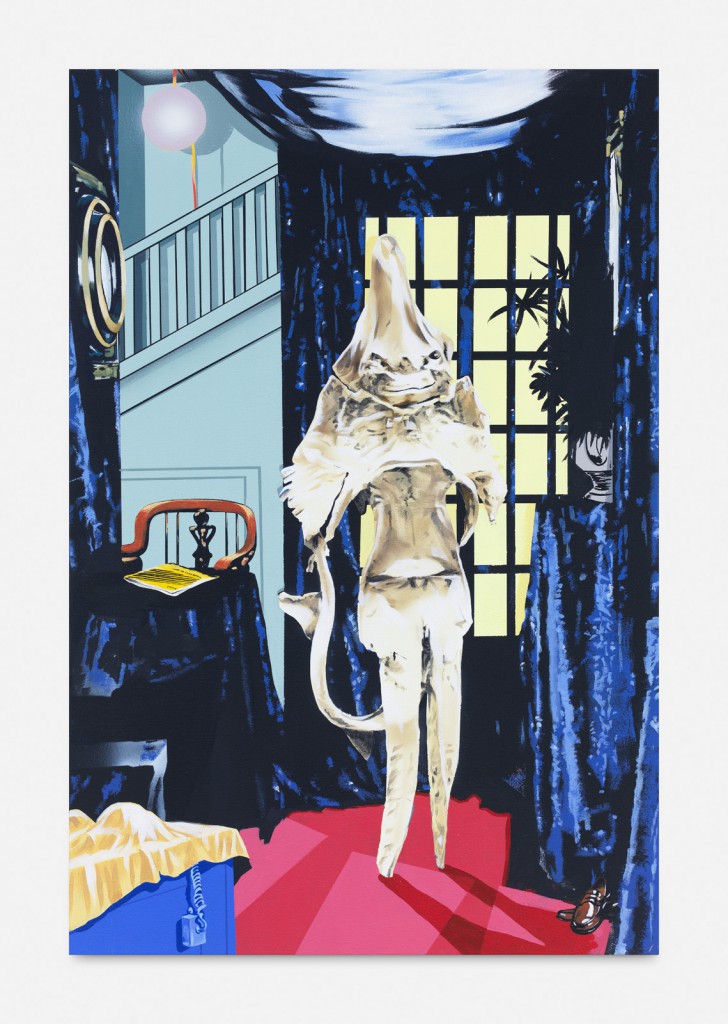

Jamian Juliano-Villani, Penny’s Change, 2015

Jamian Juliano-Villani, Penny’s Change, 2015,

What makes a painter paint? In her Bedford-Stuyvesant studio, artist Jamian Juliano-Villani uses a digital projector to create surreal paintings and discusses the graphic source material that inspires her. Juliano-Villani’s Brooklyn studio is crowded with a wildly varied collection of books ranging from 70s-era fashion, to commercial illustration, to Scientific American-style photography, to obscure European comic art. This vast image bank—which the artist began collecting in high school—generates the building blocks for her mashup creative process. “When I’m working I’ll have thirty images in a month or two months that I’ll keep on coming back to, and I’ll try and make those work with what I’m doing, but they’ll never look like they’re supposed to be together,” says Juliano-Villani. “That’s when the painting can change from an image-based narrative to something else.”

Working quickly and intuitively with the projector, Juliano-Villani toggles through a series of potential images on her laptop as a way to discover solutions for content and composition. Long attracted to cartoons, the artist borrows from illustration as a way to deflate painting’s historical pretensions and to speak in a more direct language; and yet, despite her use of vernacular imagery, what her works ultimately communicate might only be personally understood. “Painting is the thing that validates me and the thing that makes me feel good. I care about it, and they care about me. That’s why I put the things that I collect and really, really love in my paintings,” says Juliano-Villani. “They’re helping me figure out the things that I can’t communicate to myself yet.”

Her trippy acrylic paintings combine cartoonish imagery from far-flung sources, some of them actual cartoons from artists like Chuck Jones. She calls her use of other artists’ work “simultaneous exploitation and homage.”

Juliano-Villani explained her thinking in a Facebook comment: “It’s important to realize that all visual culture is fair game for artistic content, ‘appropriation’ isn’t a ‘kind’ of work, it’s almost all art. When making a painting or a print or a sculpture, it’s nearly impossible to make something without thinking of something else. A good reminder that when dealing with images 1) once an image is used, it isn’t dead. it can be recontextualized, redistributed, reimagined. 2) It should have several lives and exist in different scenarios.”

Artist: Isabelle Cornaro, Art Historian Specialised

Isabelle Cornaro, Paysage avec poussin et témoins oculaires (version II), 2009 and The Whole World is Watching, 2012

The work of Isabelle Cornaro evinces an interest in the way our perspectives are historically and culturally determined. Due to her training as an art historian specialised in 16th- and 17th-century Western art, her visual language is strongly associated with the forms and compositions of the past, ranging from Baroque and Classicism to Modernist abstraction. In her installations, casts and films, Cornaro plays with the possible meanings of everyday implements and artistic objects by placing them in a new context. Oriental rugs, Chinese porcelain, inherited jewellery; miniature landscapes, tautological objects and 16mm film.

Every now and then a single art work becomes associated with an artist in one’s mind and sticks there, obstinately refusing to cede its advantage no matter how sincerely one appreciates that artist’s entire output. Until recently, this has been the case, for me, with Isabelle Cornaro’s installation Paysage avec Poussin et témoins oculaires (version 1) (Landscape with Poussin and Eyewitnesses [version 1], 2008–9), which I first discovered in her 2008 exhibition at La Ferme du Buisson art centre in the Paris suburbs. Loosely based on a painting by Nicolas Poussin, this ‘landscape’ comprises a set of plywood pedestals of varying dimensions and tightly rolled, hung and unfurled oriental carpets, arranged according to rules of perspective and favouring a single point of view. Wandering into the three-dimensional interpretation of its two-dimensional art-historical ancestor, I discovered that the pedestals are topped with large cloisonné-patterned urns, smaller decorative items Cornaro calls ‘tautological objects’ because their forms mimic their functions (such as a duck egg-cup in the shape of a duck), as well as devices for measuring space and for aiding vision. In keeping with the perspectival organization, the size of these objects diminishes depending on their placement in the foreground, middle-distance or background. Cornaro’s accumulation of junk into the language of decoration, in a material that renders it sumptuous, suggests her faith in the innate, extraordinary power of things to endure and withstand the vagaries of how we look and see.

Cornaro uses scanning, photography and plaster casting as her methods of production. Through meticulous arrangements, she investigates the properties of objects and the historicity they can point to or steer away from. Homonyms (II) (2012), for example, are coloured plaster casts taken from soft materials such as laces, quilts and carpets. The misplaced use of colour and materiality of their new form alters their original identity and disrupts how these transformed objects are perceived. In the film, Money filmed from the side and a three-quarter view (2010), Cornraro portrays actual coins and Euro notes being transformed into abstract forms through the cinematic use of light and colour. The preoccupation with spatiality and light in the film brings currency’s aesthetic into the composition, stripping the importance of its monetary value. Cornaro creates differing landscapes in her work, welcoming new reflections on the ideology of object and space.

Osama, 2003 by Siddiq Barmak

Osama (Persian: اسامه) is a 2003 drama film made in Afghanistan by Siddiq Barmak. The film follows a pre-teen girl living in Afghanistan under the Taliban regime who disguises herself as a boy, Osama, to support her family. It was the first film to be shot entirely in Afghanistan since 1996, when the Taliban régime banned the creation of all films. The film is an international co-production between companies in Afghanistan, the Netherlands, Japan, Ireland, and Iran.

In the film, the Taliban are ruling Afghanistan. Their regime is especially repressive for women, who, among other things, are not allowed to work. This situation becomes difficult for one family consisting solely of three women, representing three successive generations: a young girl, her mother, and her grandmother. With the mother’s husband and uncle dead, having been killed in battle during the Soviet invasion and their civil wars, there are no men left to support the family. The mother had been working as a nurse in a hospital, but the Taliban cut off funding to the hospital, leaving it completely dysfunctional with no medicines and very little equipment. One foreign woman working as a nurse in the hospital is arrested by the Taliban. The mother does some nursing outside the hospital and receives payment from the caretaker of a patient, but after the patient dies the mother cannot find any more work.

The mother and grandmother then make what they feel is the only decision they can to survive: they will have their preteen daughter disguise herself as a boy so that she can get a job to support the family. Osama’s grandmother tells a story to Osama about a boy who changed to a girl when he went under a rainbow, in order to help persuade her to accept the plan. The daughter, feeling powerless, agrees despite being afraid that the Taliban will kill her if they discover her masquerade. Partly as a symbolic measure, the daughter plants a lock of her now cut hair in a flowerpot. The only people outside the family who know of the ruse are the milk vendor who employs the daughter – he who was a friend of her deceased father – and a local boy named Espandi, who recognizes her despite her outward change in appearance. Espandi is the one who renames her Osama. The masquerade becomes more difficult when the Taliban recruit all the local boys for school, which includes military training. At the training school, they are taught how to fight and conduct ablutions, and an ablution is taught to boys that should be done when they experience nocturnal emission or come in contact with their wife when they grow older. Osama attempts to avoid joining the ablution session, and the master grows suspicious of Osama’s gender. Osama realizes it can only be so long before she is found out. Several of the boys begin to pick on her, and although Espandi is at first able to protect her, her secret is eventually discovered when she menstruates.

Osama is arrested and put on trial, along with a Western journalist, and the foreign woman who was arrested in the hospital. The journalist and the nurse are both condemned and put to death, but, as Osama is destitute and helpless, her life is spared; she is instead given in marriage to a much older man. Osama’s new husband already has three wives, all of whom hate him and say he has destroyed their lives. They take pity on Osama, but are powerless to help her. The husband shows Osama the padlocks he uses on his wives’ rooms, reserving the largest for Osama. The film ends with the new husband conducting an ablution in an outdoor bath, which the boys were earlier taught to conduct after coming in contact with their wives.

Kate Cooper, Hypercapitalism and the Digital Body

Kate Cooper, Rigged 2015. Digital prints, looped HD video with sound, 6:22 min

Kate Cooper’s exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin looks at the agency of the computer generated female within the glossy aesthetics of consumer capitalism.

The work of British artist Kate Cooper inspires immediate physical and aesthetic attraction. A hybrid of consumer associations, ranging from the glossy iconography of the TV commercial and the sterility of video game graphics to the luminosity of the department store poster and the smell of freshly opened cosmetics, create a subconscious lure. Her use of CGI technology in her artistic practice surpasses a simple study of digital textures to occupy a full-fleshed, hyperreal space, usually reserved to corporate giants in advertising or entertainment.

“In the past I’ve made works where I’ve shot things with real life models, followed by a heavy amount of post-production and CGI, but this time all images are entirely constructed. I’m interested in what that entails, the labor involved and the position of those images and what they mean in terms of representation.”

Through her choice of medium and installation, Cooper employs what she calls ‘the language of hypercapitalism.’ She presents her work as billboard-size prints on light boxes similar to those found in the beauty section of any department store. Rather than simply mocking or subverting, her usage of this polished aesthetic appears more as an occupation or redirection of capitalist mannerisms. “It’s very interesting just getting your hands dirty in finding your own agency within this glossy language, to be able to produce it yourself. When working with this technology, I always feel there’s a kind of hacking element to it.”

Cooper’s work expresses an ultimate devotion to and faith in the digitally constructed body. There is a subtle but crucial shift in the discussion on agency and labor within a digital space – surpassing representation, these bodies are now only representative of themselves.

The fetishization of the CG model’s body alludes to the power of the post-representational female subject; the model has her own body with full potential action rather than being merely a representation of a body. She is a she, not an it. “For me, images are no longer representational in themselves,” Cooper adds, “they perform another function, and I’m interested in exploring the possibilities of what that agency could be, what that could produce. It’s very exciting.” By creating models (rather than images) Cooper insists that agency is central and becomes the politicized premise of the work itself.

Resort 2016: Louis Vuitton by Nicolas Ghesquière

Louis Vuitton by Nicolas Ghesquière, Resort 2016, 2015

The Resort season has turned into a mini architecture tour. Karl Lagerfeld set up Chanel operations at Zaha Hadid’s Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul on Monday. Raf Simons will show Dior at Pierre Cardin’s south of France home next week. And today Louis Vuitton had over 800 rooms booked in Palm Springs, California, for the celebrities, international journalists, and clients that assembled here to witness Nicolas Ghesquière’s latest LV collection at the Bob Hope estate. The designer first laid eyes on the Bob Hope house 15 years ago on his earliest trip to this desert city; it made a lasting impression. Driving up to the place this evening, it was easy to understand why. The John Lautner-designed house (which is for sale, by the way, with an asking price of $25 million) is perched on one of Palm Springs’ central peaks. The views of the valley below are breathtaking, but the house itself is a scene-stealer, a hulking 23,000-square-foot marvel that, depending on the vantage point, looks like a grounded spaceship or a volcano but is decorated on the inside in what Ghesquière described as a sweet ’50s style. “The paradox of the brutalism of the architecture and the refinement of the interior was quite inspiring to me,” he said. “I love the idea of sweet and hard at the same time.”

That idea played out in the clothes. But first, a word about the setup, which was choreographed down to the minute. As the 500-odd guests milled around on the lawn, the gong that rings at the Fondation Louis Vuitton could be heard, establishing a connection between Paris and Palm Springs. A drone hovered overhead, capturing footage for the live-stream. And the 6:15-on-the-dot start time capitalized on the magic hour light before the sun dipped below the mountains behind the house. Plywood and Plexiglas stools were arrayed on the terrace below the swooping copper roof, and as the models began their exits, they could be seen walking across the house’s second floor and descending the staircase through well-placed windows. They circled the pool before making a circuitous path in front of a crowd that included Kanye West, Catherine Deneuve, Michelle Williams, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and Grimes.

The lineup’s big news was its silhouette. Ghesquière set the current trend for A-line miniskirts in motion with his first Vuitton show 14 months ago, a fact he’s no doubt aware of. He pivoted here, sending out maxi skirts on desert boots paired with blousy cropped tops crisscrossed by leather belts that exposed a triangle of midriff. It was a directional look that had just a touch of the 1930s Hollywood starlet to it. From there, he was off and running, alternating printed and quilted silk housecoats like something a Palm Springs granny would wear with leather motocross jackets that inevitably called to mind the upcoming reboot of Mad Max. A black-tie-ready beaded scuba jacket and sporty, tailored trousers intermingled with printed eyelet prairie dresses that he suggested nodded in the direction of Altman’s classic 3 Women. And then there were the hot pants, cut high on the thigh and worn with everything from an army sweater to zip-front silk blouses to a boxy suede jacket.

Ghesquière has spent his first year and change at the brand developing his signatures, and despite the far-ranging feel of this show, he didn’t abandon them here. The oversized front zips he’s used from season one reappeared, as did the suede color-blocking and the metal studding. As usual, he made the most of the house’s leather know-how, cutting the maxi skirts in a leather so liquid it could be mistaken for silk, choosing a sturdier weight for a dress that he embellished with the four-pointed fleurs of Vuitton’s iconic monogram, and, most spectacularly, embroidering glossy swatches of the stuff in a snakeskin motif on a long, lean column of body mesh. As strategic as he remains, the collection’s lasting impression was its uninhibited sense of play; and the reaction was unanimous, this was Ghesquière at his most Ghesquière: experimental and unconstrained. California suits him.

Written by Nicole Phelps,

http://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/resort-2016/louis-vuitton

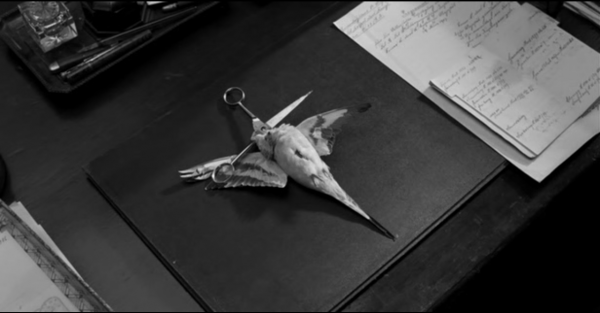

The White Ribbon (2009), About the Roots of Evil.

The White Ribbon is a 2009 black-and-white German-language drama film written and directed by Michael Haneke Das weiße Band, Eine deutsche Kindergeschichte, “The White Ribbon, a German Children’s Story”, darkly depicts society and family in a northern German village just before World War I and, according to Haneke, “is about the roots of evil. Whether it’s religious or political terrorism, it’s the same thing.”

The film premiered at the 62nd Cannes Film Festival in May 2009 where it won the Palme d’Or, followed by positive reviews and several other major awards, including the 2010 Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film also received two nominations at the 82nd Academy Awards in 2009: Best Foreign Language Film (representing Germany) and Best Cinematography (Christian Berger).

In Oberösterreichische Nachrichten, Julia Evers called the film “an oppressive and impressive moral painting, in which neither the audience nor the people in the village find an escape valve from the web of authority, hierarchy and violence. […] Everything in The White Ribbon is true. And that is why it is so difficult to bear.”

Markus Keuschnigg of Die Presse praised the “sober cinematography” along with the pacing of the narrative. Keuschnigg opposed any claims about the director being cold and cynical, instead hailing him as uncompromising and sincerely humanistic. Die Welt’s Peter Zander compared The White Ribbon to Haneke’s previous films Benny’s Video and Funny Games, both centering around the theme of violence. Zander concluded that while the violence in the previous films had seemed distant and constructed, The White Ribbon demonstrates how it is a part of our reality. Zander also applauded the “perfectly cast children”, whom he held as “the real stars of this film”.

“Mighty, monolithic and fearsome it stands in the cinema landscape. A horror drama, free from horror images”, Christian Buß wrote in Der Spiegel, and expressed delight in how the film deviates from the conventions of contemporary German cinema: “Director Michael Haneke forces us to learn how to see again”.

Performance Artist: Tris Vonna-Michell

The Trades of Others, 2008, and Finding Chopin: Dans l’Essex, 2014

Through live performance and audio recordings of spoken texts, Vonna-Michell relays circuitous and multilayered narratives that combine personal anecdotes and historical research. Vonna-Michell’s narrative structures are characterized by repeated detours, dead ends, and streams of association. Dense conglomeration of photographic material, from film and slide projections to photographic prints and other ephemera form a “visual script” that is animated by the artist’s recitations. Integrating fiction and factual information, Vonna-Michell’s narratives address the nature of coincidence and contingency, often referencing his personal history and artistic production. His practice builds on a process that is both recursive and prospective with images drawn from his own archive, including those from previous works, continually reappearing in new configurations.

By splicing the lived with the learnt, Vonna-Michell’s stories and actions form a personal analogue to that monumental act of dispersal and investigation: the large-scale destruction of documents by Stasi officials in 1989, and the new government’s subsequent commissioning of archivists (nicknamed ‘the puzzlers’) to reassemble the mountain of some 600 million scraps. For a month in 2005 Vonna-Michell holed up in a GDR-era Leipzig bed-sit alone with his personal archive of photographs, taking 36 exposures of each image before painstakingly shredding each one by hand. This fragmented portfolio was later presented at his Glasgow School of Art degree show, the resulting photographic slides now used in performance, mementoes of a partial re-enactment and an end-point to his earlier body of work.

Other objects that Vonna-Michell uses in performance have an insufficient and temporary quality: in hahn/huhn, a conspiracy thriller that ducks into the tunnels rumoured to lie under Berlin’s Anhalter Bahnhof, three blocks of dry ice squat in a line between artist and listener, chilling the feet and offering a shonky reminder of the Cold War and the Berlin Wall; episodes in Finding Chopinare represented by a newspaper clipping, an egg carton and a stick of rock. So ephemeral are these carefully gathered props that many were allegedly stolen during an exhibition in Brussels in 2006, after which the artist replaced them with a seven-inch vinyl recording, Short Stories & Tall Tales (2007). The record is the only saleable item Vonna-Michell has produced to date, the token of a failure to maintain an archive that yet gestures towards the continuing possibility of circulation. An archive attempts a totalizing collection of information, but what if, as in the case of the Stasi, it is kept safe or destroyed, hoarded or dispersed?

Vonna-Michell’s practice reflects on the possibility of recording and transmitting history through the spoken and written word, tracing the associative complexities of how histories and rumours are told.

Tris Vonna-Michell lives and works between Stockholm and Southend-on-Sea in the UK. Recent solo exhibitions have been organized by VOX Centre de l’Image Contemporain in Montreal, T293 in Rome, Jan Mot in Brussels, Capitain Petzel in Berlin, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, Metro Pictures in New York, and Cabinet Gallery in London. Vonna-Michell’s work has been included in exhibitions at the Tate Britain in London, Moderna Museet in Malmö, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Secession in Vienna, the Shanghai Biennial, and the Yokohama Triennial. Vonna-Michell was nominated for the 2014 Turner Prize, and was awarded the Baloise Art Prize and Ars Viva Prize for Fine Arts in 2008. He studied at the Glasgow School of Art, the Städelschule in Frankfurt, and Emily Carr University in Vancouver.

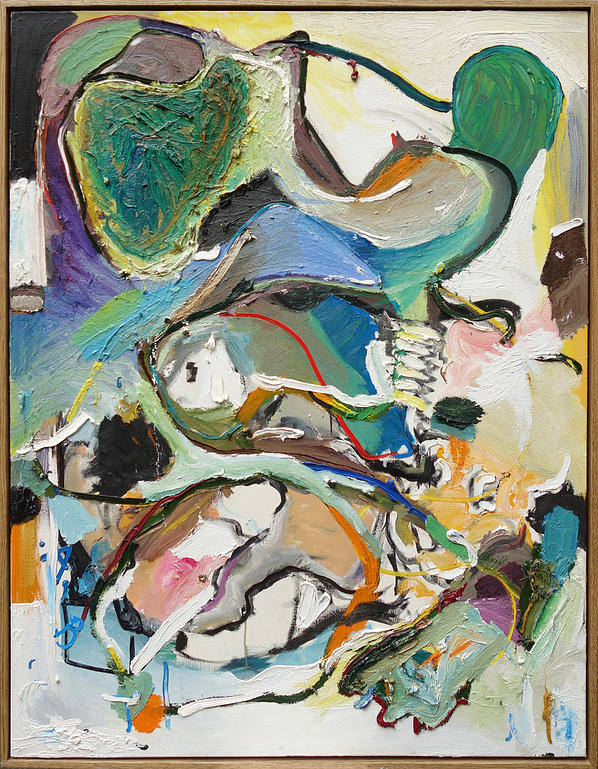

Norwegian Painting: Christian Tony Norum

Christian Tony Norum, Installation view, Untitled, 2015 and Colours of All Time, 2015

A beautiful bird, a drum, the stars and the ancestors, a river, the sea, the wind and the sun. I am blinded by being a human being, searching wondering about everything and nothing. I am a universal human being that live and breath for art, poetry, performance. My main focus is painting but with all this intensity and shadow, I even have to use my self as a medium.

The problems I’m dealing with or try to solve, is how a specific painting or situation have any value or effect at all in this world. I cant change the world or solve any big problems but only believing that small organs like a catalyst can present some kind of nerve that show a little hope of healing in all this killing. Ambitious initiative, which addresses issues of storage and research in addition to exhibitions, museums-represents a substantial attempt to cement this reputation.

Possibilities available for the fundamental artists to negate, stripping away until nothing remains, or to accumulate, to embrace additively until one has reached the limit of fullness. The subversive, at the times contrarian loving and caustic, chaotic and prec—has pursued both paths at once both tendencies arc visible in the presents of artistic practice.

Working with painting, performance and sculpture I need to examine strategies and issues in post structural and modernist theories by using dialogue and communication with my contemporaries and earlier artist.

I use the art-history as a innocence open source to use this old knowledge as a catalyst for new deeper meanings and generate it into a self-reflecting understanding of how I preside the world.

Its not always a issue, its to amuse your self in this reality of ours.

The issues that already exist, or you are put into this world and by using experimental natural methods to meet this experiences with closed eyes while staring at the sun and you know what it is for what it is and that is the color orange.

Artist, Sascha Weidner, Photographer, 1979 – 2015

Sascha Weidner, Am Wasser Gebaut, 2009, Lay Down Close By, 2012 and La lutte de J. Avec l´ange, 2006.

Sascha Weidner was a German Photographer and Artist, who lived and worked in Belm and Berlin. The work of Sascha Weidner deals with the creation of a radical subjective pictorial world. His photographs are characterized by perceptions, aspirations and the world of the subconscious. His work has been exhibited and published internationally. Sascha Weidner died suddenly at age 38.

“It’s not about putting pictures on the wall. I use the room to tell my story, to create a theme, a storyline, underlined by a romantic melancholy. It’s totally authentic, like I am. A lot of times, it’s also too much, like I am. Feeling too much and speaking too much.”

In his essay ‘What Is the Contemporary?’ the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben argues that contemporaneity is defined not by being attuned to one’s times but, on the contrary, by being disconnected and out of touch. For Agamben, the contemporary is precisely that which contrasts with the present so sharply that the latter’s contours become visible. I was reminded of Agamben’s thesis when visiting Sascha Weidner’s exhibition, ‘The Presence of Absence’. The show presented a wide variety of media and topics, ranging from photographs taken in a forest in Japan to sculptures referencing a family in Germany. There were also light-boxes and collages, pictures of graffiti and cherry blossoms. What connected each of the works, however, as the exhibition’s title made clear, was a concern with developing procedures to envision the invisible and the attempt to find traces of the past in the present.

Central to the exhibition was a series of photographs Weidner shot while hiking in Aokigahara, a forest at the base of Mount Fuji in Japan. Rumoured to be so dense that no one who enters it ever leaves, it has long been the subject of Japanese mythology, inspiring folk tales, as well as appearing in modern literature, including a novel by Haruki Murakami. It is also a prime spot for suicides. Weidner followed the paths of people who entered before him, documenting traces of the journeys of those whose travels went unnoticed. Many of these photographs were sparsely and unevenly illuminated, reflecting the maze-like density of the forest, as well as alluding to the frail spirit of the wanderers. They included images of the ribbons people attach to branches every few metres in case they change their minds and want to retrace their path (Atropos II, 2013); bits of rope and plastic left to rot (Untitled, 2014); crushed red berries in the snow (Untitled, 2014); and the shadows of trees (Untitled, 2013). The idea was simple (sort of old-school Existentialism, in fact) and the execution expertly straightforward (some Romanticism here, some Pictorialism there). Yet, by showing both what Weidner’s predecessors on these paths might have seen and, at the same time, documenting what remains to be seen of them, the work was incredibly powerful – and, perhaps above all, complex – creating a mythological emotional territory of very real terror. Indeed, the closest parallel I could think of was Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary film about the Indonesian mass executions in the 1960s, The Act of Killing (2012).

The works in the show all articulated the presence of an absence by providing the contours of that absence, the ghosts of a past. In the moving looped video The Presence of Absence II (2014), a Chinese man dances a waltz on his own, his arms wrapped around an invisible woman (whose bag may still be visible in the margins of the screen). And the series of collages titled ‘Ecken’ (2014) features photo corners that no longer secure any photos, now functionless, they inevitably recall their prior use. They call to mind the notes that the elderly Immanuel Kant used to try to drive a particular person from his memory, writing: ‘The name Lampe must be completely forgotten’ – a method that was, of course, entirely self-defeating.

Weidner’s exhibition proved itself contemporary – in a time of simulacra and algorithms, of Post-internet art and Ulrich Beck’s ‘risk society’ – by sincerely reintroducing the ‘real’, retracing it as if it were still out there, an invisible thread to be revealed and unravelled. Of course, the artist understands that, after Jean Baudrillard and the post-structuralists, the ‘real’ is no longer an unproblematic register if, indeed, it ever was. But it can be experienced nevertheless, he seemed to suggest, as an affective performance. Weidner’s photographs and collages, his video of the dancing man: they all perform reality as mourning, an acting-out of the present by way of a script from the past, looking forward while feeling backwards. In this, they are a performance of contemporaneity itself – precisely in the way described by Agamben, connecting to the present by not being of it.

Written by Timotheus Vermeulen, published in Frieze, Issue 169, March 2015.

Erika Vogt, Slug, Simone Subal

Erika Vogt, Stranger Debris Roll Roll Roll, 2013 and installation view of Slug, 2015

Erika Vogt might alternately be described as a sculptor, printmaker or video artist, but, like so many of her peers, these labels merely point at the edges of something deeper. Born out of the tradition of experimental film, Erika brings to bear many of the techniques from that practice to her sculptures and installations – collaging, layering and cutting up different material.

Erika Vogt, born 1973, is a Los Angeles based artist represented by Overduin & Co. in Los Angeles and Simone Subal Gallery in New York City. She received an MFA from California Institute of the Arts and a BFA from New York University.

Vogt uses a range of media and techniques in order to explore the mutability of images and objects. Within her installations, she fuses elements of sculpture, drawing, video, and photography to produce multilayered image spaces. She challenges prescribed art-making systems, conflating and confusing their logic, as sculptures take on the properties of drawing and photographs take on the nature of film. Building on her background in experimental filmmaking, Vogt’s visually dense videos combine both still and moving images, digital and analog technologies, and playfully incorporate drawings and objects from her previous projects. In her recent work, exemplified by installations such as Notes on Currency (2012), The Engraved Plane (2012), and Grounds and Airs (2012), Vogt took as her subject the ritual use and exchange of objects, such as currency, and investigated the empathetic relationship between objects and people.

To read Slug through this gift of words (albeit someone else’s) as “an extension of the interior life of the giver, both in space and time, into the interior life of the receiver” allows us to perceive the slug in its dialectical sense: as a $50 gold coin, for sure, but also its opposite, a counterfeit, a token used to subvert a slot machine’s understanding of exchange value. We experience Slug as the implicit trace of productive activity, but it also transforms us (the viewer) into the slug, the interval between things, the breath or gap. “But blank lines do not say nothing,” as Carson writes.

Through her work, Vogt attempts to gesture towards community. Not in the educational sense or what we conflate with “social practice” as an institutional turn, but in the old way, the way it used to mean friendship, comradeship, living and working together. The sculptures shade, point, protect and interact with each other, creating new perspectives on and for one another. Bringing to mind Shelly Silver’s Things I forgot to tell myself, in which the filmmaker’s scrunched up hand forms an aperture through which we see the city, we should read Slug together. It is through their implied social relation that these objects reveal sincerity. Vogt refuses to take the stance of either cynical embrace or pseudo-rebellious anti-art, meaning there is instead an untypical openness to the work. It yearns to protect, to support.

Source: Art News, September, 2015.

Political Culture: Eugenio Grosso, The Long March

Eugenio Grosso, The Long March, 2015.

Refugees walk. Their aim is to reach the destination as soon as possible and when there are no public transportation (or they are not allowed to use any) walking is the only choice. In an endless journey that takes months, or even years, moving is the main need and the only thing that matters. They never stop and when they are forced to, it brings distress and desperation.

Same as in the Bible these people are forced to leave their houses and wander in the desert until they will reach a place where to settle down and start a new life.

They travel the old way, a step after another, in the manner of the ancient human beings.

Their footprints on the ground are traces of a mass migration on invisible routes passing next to our cities and houses. Refugees are often ignored and always moving, they are like traces in the sand that are easily cancelled.

Sicilian born Eugenio Grosso moved to Milan at 18 to study BA Scenography at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, graduating in 2007 with honours. He has first worked as a part-time commercial photographer since 2007 and then as full-time photojournalist since 2009.

Grosso is a regular contributor to Italian publications such as Corriere della Sera, la Repubblica and la Stampa. His work has been featured on international publications like the Guardian, the Telegraph, the Financial Times, the BBC and the Washington Post. He lives and works in London.

Photography: John Divola

John Divola, Theodore Street, 2012, San Fernando Valley, 1973 and Zuma Beach (1978/2006), 1978

“Abandoned houses are one of the few places where you can go and paint anything you want and nobody is going to yell at you” says John Divola.

Los Angeles–based photographer John Divola is perhaps best known for this series of photographs documenting the gradual destruction of an abandoned and oft-vandalized beachfront property at Zuma Beach in Malibu. Without a studio of his own in the 1970s, the artist roamed Los Angeles in search of vacant properties that he could photograph. Using them as his canvas, he sometimes spray-painted his own designs onto their interiors, photographing them before the buildings were destroyed. Reflecting his painterly manipulation of the physical site, Divola’s Zuma photographs skillfully frame spectacular sunset views within these dilapidated structures, making his visually compelling, color-saturated photographs more than just pure documentation.

Divola has taken his camera into a variety of environments over the past four decades. However, it’s the vacant, dilapidated home that have been a constant throughout his career. He has found the structures in the San Fernando Valley and in the shadow of Los Angeles International Airport, along the coast at Zuma and deep into the Inland Empire. The modern ruins provided a studio when Divola couldn’t afford one. Divola could add to a scene that already existed, perhaps with a few strokes of a paintbrush, and then photograph it. They remain a part of his work, even now that he has his own space amidst the business parks and storage units of Riverside. Ultimately, these venues held an intrigue that went beyond practicality.

“It wasn’t a blank canvas,” says Divola. “It was something that already had a sense of place and presence and prior activity.”

It’s the activity that captures Divola’s eye. “If someone kicks a hole in the wall,” he says, “I’m really interested.”

Fitness for Artists, “We can finally meet in a virtual space and get fit for life together.”

Helga Wretman, Fitness for Artists, 2015

Helga Wretman aims to fill the body and soul of participating artists with endorphins to improve their creativity and self consciousness, whilst providing a platform for international artists to connect with peers in other parts of the world. “We can finally meet in a virtual space and get fit for life together.”

12 artists have been invited to represent their country, themselves as artists and their will to communicate. This will be a performance where no participant is passive.

The class begins gently with an organic warm up of the joints and major muscle groups that prepares your body for more intensive stages. There after we move on to the activate the cardiac functions in your body. That will start with some fun sparring in couples and then we do some classic aerobic and end with an intensive Jump-style tutorial. At this stage we are warm and ready to move on to the muscle training and floor-work without weights, including yoga and various classic body toning and strengthening exercises. To end the class we make a stretching session focusing on both big and small muscle groups.

Helga Wretman (born 1985 in Stockholm) lives and works in Berlin. She completed her training at the Kungliga Svenska Balettskolan in Stockholm for Modern and Contemporary Dance. Helga has also studied dance in London, Berlin and Stockholm.

Wretman has performed in venues such as Peres Projects, Berlin; Darsa Comfort, Zurich, and Kunsthalle Athena, Athens. She has also performed for artists such as Aids- 3D, Jeremy Shaw, Donna Huanca, Peaches, Reynold Reynolds as well as performing in numerous German films as a stuntwoman.

Artist: Oliver Laric

Oliver Laric, Touch My Body, Green Screen Version, 2008 and The Marble Player, From the series Lincoln 3D Scans, 2013

Oliver Laric uses memes, movable type, copies and collective agency to make art that is only partly ‘his.’ Oliver Laric once showed a 16th-century print by Flemish court artist Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder. The etching depicts a scene of iconoclasm, or Beeldenstorm, during the Reformation, when churches and public spaces in northern Europe were systematically purged of religious imagery, often by mobs. Hallucinatory in its detail, the print shows a swarm of figures on a mount pillaging icons, breaking statues, tossing altarpieces into a fire. Birds in the air shit on monks beside bare trees that crown a bald outcropping; broken relics and shattered crucifixes jut out like gravestones from a pit.

Gheeraerts’s work isn’t simply a depiction of image breaking. When viewed from afar, the mass of active figures in the print forms a new, anamorphic image: a grotesque, composite illusion of a monk’s rotting head. An assembly of small bodies forms a sagging mouth (full of drunken townsfolk), and a group of monks ploughs a field that’s also the head’s wrinkled brow; a monkey stands inside an ear, and the figure’s nose is formed by a crucifix about to be toppled between two hollowed-out eye sockets.

I don’t think Laric had ever seen the real Allegory of Iconoclasm (c. 1560–70) – which exists only as a smallish, unique print in the British Museum – when he introduced me to Gheeraerts’s work during a conversation about his own video Versions (2012), the third in his series of that name, in which the monk’s head appears briefly. I write ‘real’, although Laric’s information-driven videos and sculptures confound distinctions between real and fake, even making that effacement their subject. I write ‘own work’, despite Laric’s ongoing concern with the mutability of authorship and ownership. An author is fungible, particularly as enabled by recent forms of collective and participatory labour. Internet memes, popular and children’s films, super-cut YouTube videos, medieval sculptures, outsourced remakes and the ‘participatory’ labour practices of North Korean monuments are all found, re-remixed and translated in Laric’s works. And although I write ‘conversation’, that word only partially accounts for the hopscotching, hyper-medial surge of links, flickering images and n+7 web results that the artist retrieves, combs through and reassembles to display and comment on his own material, as well as that of others. ‘I sometimes Google terms that seem to have nothing to do with each other,’ Laric says. ‘“Mikhail Bakhtin and prosumer” or “Samuel Beckett and Teletubbies”. Usually, there’s an unexpected link.’ In the latter case, it might be Beckett’s Quad (1981), whose four actors could be proto-Teletubbies; in the former, it’s Bakhtin’s dialogic understanding of how production oscillates between collectives and individuals – a dialectical motor Laric puts to work in his collectively-based pieces.

There is no distinction between the material Laric finds and that which he presents as his own. Laric’s exhibition ‘Kopienkritik’ (Copy Critique) at the Skulpturhalle in Basel in 2011 took its cue from the 19th-century methodological approach to philology and ancient sculpture, which viewed (inferior) Roman ‘copies’ in terms of (superior) Greek ‘originals’, reconstructing those lost originals via the bulk typologizing of inferior later copies. Laric cast and grouped that museum’s collection of Greek and Roman plaster casts into typologies, alongside video monitors and heads cast by the artist. ‘Copyright did not exist in ancient times, when authors frequently copied other authors at length in works of nonfiction.’ This declaration does not come from a history of literary influence, but from the GNU Manifesto, written by MIT’s Richard Stallman in 1985 to announce an influential, free software, mass collaboration coding project (and the theoretical backbone to much open-source digital content today). ‘Be promiscuous,’ reads an Open Source Initiative manifesto encouraging coders to distribute their works free of charge. Laric draws on this ethos of collective reworking.

Although you can find it on YouTube, Laric’s Touch My Body: Green Screen Version (2008) is not really a video but rather a participatory game, or dare, that Laric intended to be appropriated and modified. For Touch My Body…, Laric stripped Mariah Carey’s music video for her 2008 song of the same name of all but Carey herself, and replaced it with a green screen, against which any background could be inserted. When Laric posted the piece to YouTube that year, users took the cue and began uploading amateurish, witty remixes using Laric’s template. (Including one with a background of zombie gore taken from Sean of the Dead, 2004). Today, the first result when searching for Laric’s piece on YouTube is not his original video, but an amateur mash-up, of which there are many.

Memes – like fame, lies and capital – accrue value and cachet as they circulate. But they also date and flatten, and while Touch My Body … lacks the complexity of Laric’s later pieces, it demonstrates the atmosphere in which his work arose: the newly ‘social’ internet; the advent of the ‘prosumer’ (‘producer-consumer’ or ‘professional-consumer’) technology that enabled easy editing by 15 year olds; online video-sharing platforms; freely accessible, though commercial, image repositories such as Getty Images and Flickr. On a larger scale, the points of departure for Laric’s works have been incipient shifts in group structures and collective agency (shifts not limited to the internet), the global political atmospheres of what in the mid-2000s began to be called ‘truthiness’: a simultaneous reliance on, and distrust of, circulated images and narratives.

The striking succession of historical images that opens the first of Laric’s essayistic video series ‘Versions’ (2009–12) is as much a comment on political shilly-shallying as an assertion of the masses’ new claim on image production and circulation. The video, which is a trove of examples of the fraught status of reproductions and copies from recent and contemporary material culture, begins with an image (released by Iran’s state media to Agence France-Presse in 2008) of four missiles, which was used to illustrate Iran’s missile tests when it appeared on the pages of the Los Angeles Times and the Financial Times, among many others; following this, Laric inserts a graphic that indicates how that image was clearly manipulated, if not fabricated, using Photoshop (the multiple missiles are effectively copy-and-pasted from within the image). And finally, a series of user-generated spin-offs of the Photoshopped image showing dozens of missiles, their streams in comic curlicues. I can’t think of any better way of exemplifying Jean Baudrillard’s ideas about simulacra and hyperreality in our age of truthiness than this simple slideshow compiled by Laric.

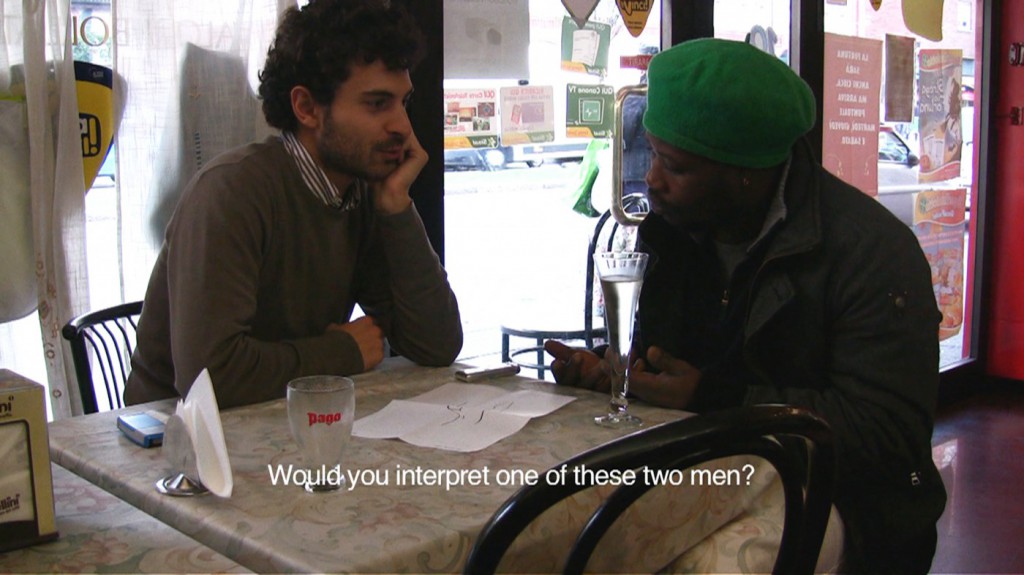

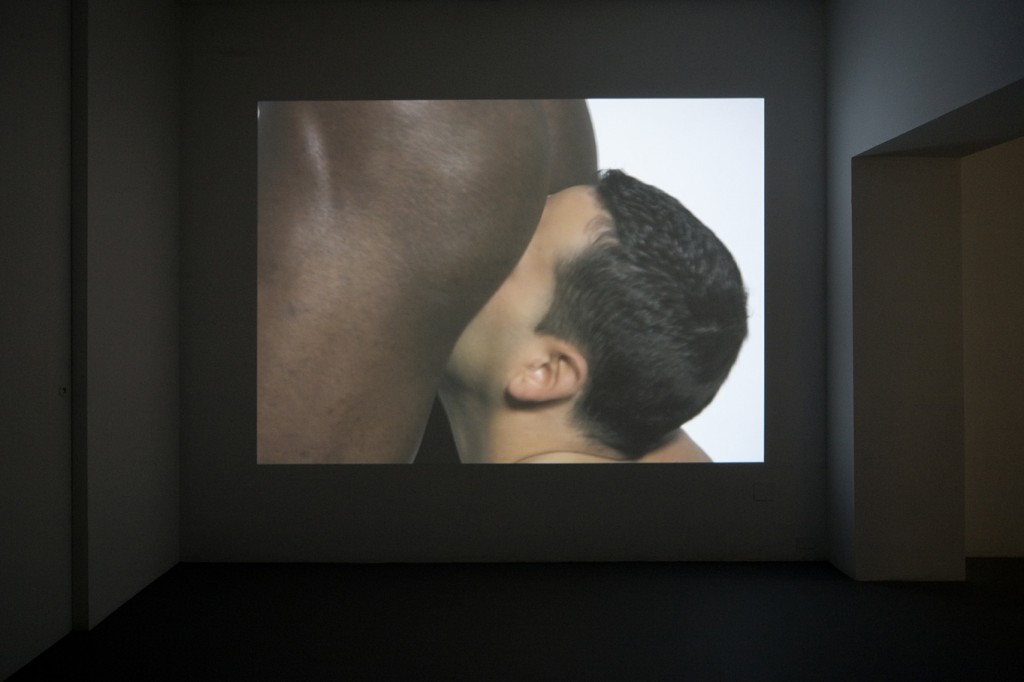

Patrizio Di Massimo: Col Sole in Fronte (With The Sun In Front Of Me)

Patrizio Di Massimo, Col Sole in Fronte (With The Sun In Front Of Me), 2010

Col Sole in Fronte (With The Sun In Front Of Me) begins on the ground floor of the gallery with the video Duets for Cannibals. This work was commisioned by Milan City Council and Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation in order to make a portrait of an African boy, Abdullay Kadal Traore, who has been living in Italy for several years. I accepted that request but not standing behind the camera and filming Abdullay as an exotic subject. The video becomes thus a dialogue or a duet in which we reason together about staging my proposal for the commission that he initially accepts and then rejects, revealing the intrinsic limit that we are not disposed to go beyond although we are both paid.

On the first floor, the exhibition continues with a double video installation Faccetta Nera, Faccetta Bianca (Italian, Little Black Face, Little White Face). The drawing that I showed to Abdullay in Duets for Cannibals becomes an image through the use of two actors and a photography study. The video installation examines the problem of difference with a dichotomic and literal attitude, and it gains its real meaning when is combined with the mistaken interpretation in the songs in question. In fact, Faccetta Nera was composed in order to attribute a noble motivation to the Ethiopia’s colonial invasion (1935) encouraging the Italian and the Abyssinian to unite; while Faccetta Bianca was the subsequent request of the regime that didn’t relish the first song. Facceta Bianca attempted to overturn it, however it did not gain a general acceptance among those who still sing Faccetta Nera identifying that “Black” as the ideology colour. Faccetta Nera, Faccetta Bianca:

If you look at the sea from the hills/Young negro slave amongst slaves/Like in a dream you will see many ships/And a tricolour waving for you/Little black face, beautiful Abyssinian/Wait and see the hour coming!/When we will be with you/We will give you another law and another king/Little black face, beautiful Abyssinian/Our law is slavery of love/We will take you to Rome freed/YOU WILL BE KISSED BY OUR SUN/and a black shirt you will be too/Little black face, you will be Roman/Your only flag will be Italian!/We will march together with you/and parade in front of the Duce and the king

Little white face, when I left you/That day on the pier in the steam/With the legionnaires I embarked/And your black eye gazing at the heart/It was equally moved as mine/While your hand was saying goodbye to me/Little white face, my love/Goodbye little, pale, tired face!/Little white face, one goes where one’s already been/in the trench, already on my mind again/among so many misty faces/IS YOUR LITTLE FACE, BRIGHTER THAN THE SUN/Nearly contrasting these black faces/your sharpshooter is a flame and a light/Little white face, my only passion/The day the sharpshooter will clasp you tightly to his chest with emotion/will come/Little white face, one goes where one’s already been/And your little, beautiful, white face/Will rest on a tired medal!

The exhibition pertains to the sun, that is said to be Italy’s petroleum, to our heads and faces, to the intensive dialogue between the Italian contemporary society and its specific colonial past. The Italian song, through its use and quotation, interweaves all the works in the show and expresses historical, cultural and image ties. The exhibition also includes a rich selection of drawings made in 2009.

Col Sole in Fronte is then this press release that explains itself as an artwork within the exhibition. It explains and extends itself all around looking for that place in the sun which is Italy, which should be Italy, but has never been.

Go…my heart, from flower to flower/with sweetness and with love/go you for me…./Go…since my happiness/WITH THE SUN IN FRONT (OF ME)/and happy I sing/blissfully…/I wanna live and enjoy/the air of the mountain/’cause this enchantment/costs nothing!/Ah, ah! Today I ardently love/that impertinent creek, minstrel of love/Ah, ah! The blossoming of the trees/keeps in feast this heart/do you know why?/I wanna live like this/with the sun in front (of me)/and happy I sing/I sing for me!/Ah, ah! Today I ardently love/that impertinent creek, minstrel of love/Ah, ah! The blossoming of the trees/keeps in feast this heart /do you know why?/I wanna live like this/ with the sun in front (of me)/and happy I sing/I sing for me!/