Yvonne Venegas, From the series El Tiempo Que Pasamos, Inédito, 2006 and Maria Elvia de Hank, 2006-2010

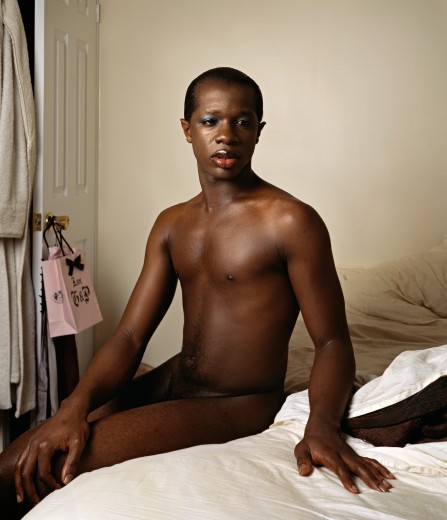

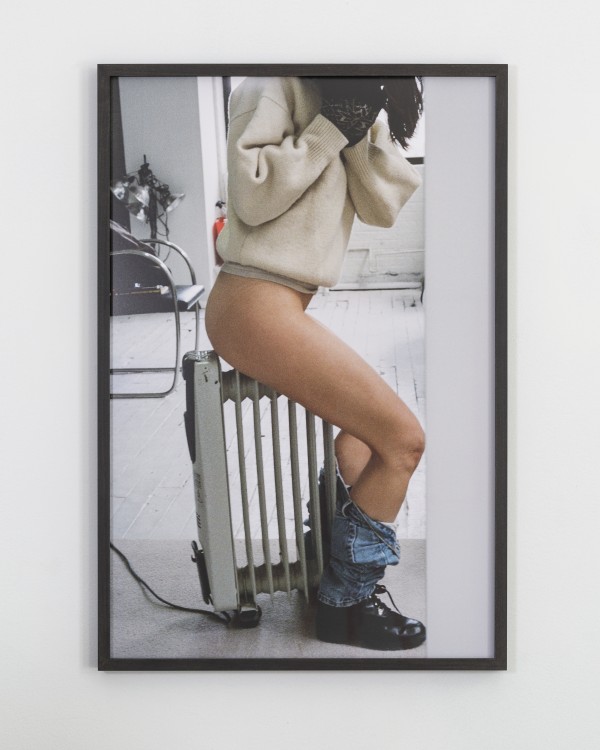

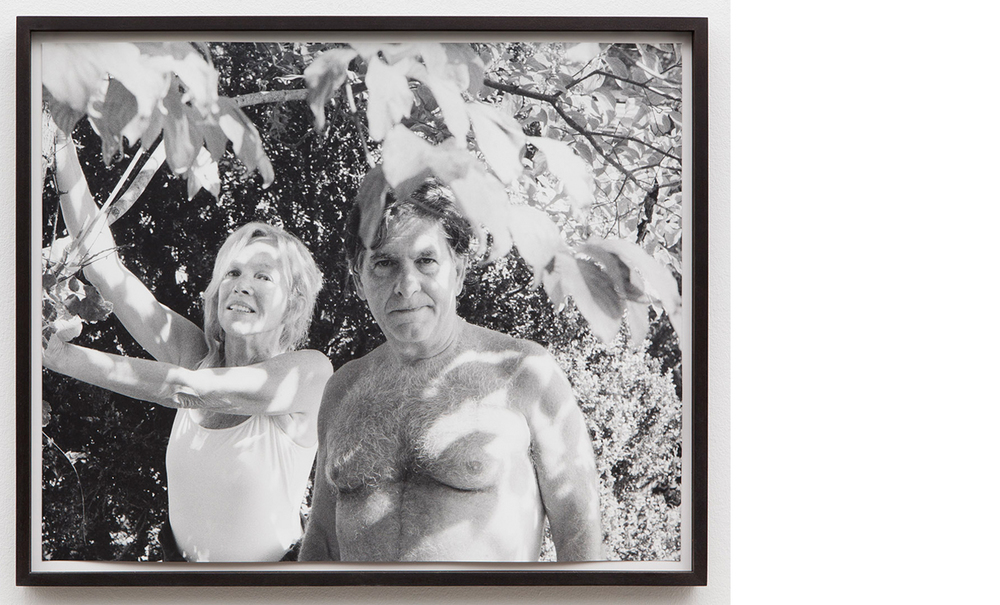

Over the years, Yvonne Venegas has a developed a specific visual language through her photographs which thrive on moments of fleeting imperfection. She captures her subjects in flux, scenes that reveal artifice, and various states of becoming. Venegas balances beauty and composition with ideas of the absurd. She finds substance beneath layers of pretense and turns a critical gaze toward the superficial. It should be noted that Venegas does not focus on the unsavoriness of her subjects rather she unconvers moments of tangible realness and underscores the human condition.

“Growing up with my father was not simply to be the daughter of a social photographer, it also meant to live with somebody who wanted to belong to the particular social class, that took effort for him to accommodate himself within. In that effort I saw the clients come in and out of the studio and I assisted many weddings, not as a guest, but as a child. My participation in people´s events was not something I enjoyed, but it was almost viewing something foreign with an added feeling that it could never be mine. […] In photography I have found a way to make moments, people and situations my own. So if compared, my dad´s and my reason to photograph were very different: his had to do with a need for money and mine had to do with a need to see things my way.”

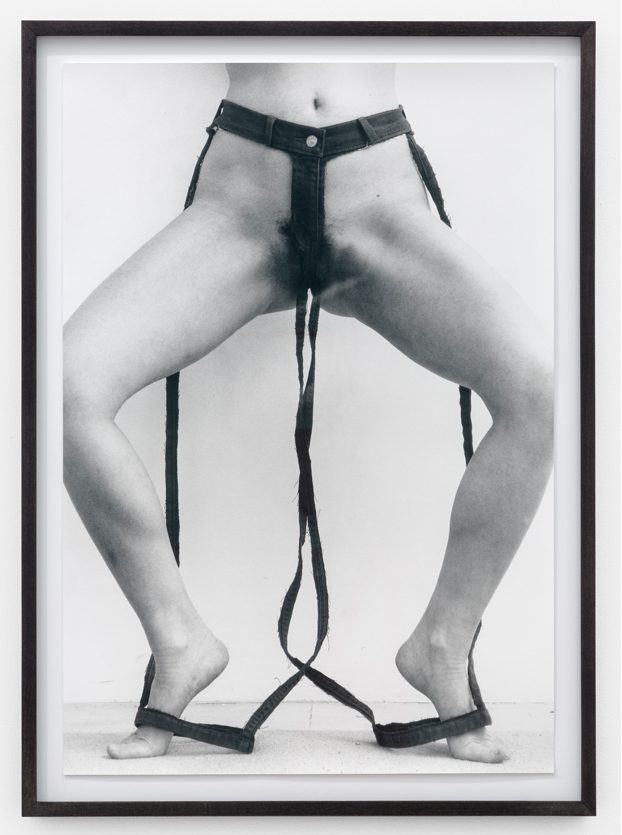

The images produced by Yvonne Venegas tend to be betrayals: efforts to snap the shutter a split second before or after the subject’s awareness takes control of the image. This untimeliness is on various occasions a fruit of parasitism: capturing one model while being photographed by another, the eruption of the lens standing in an unresolved parallax against a scene constructed by someone else.

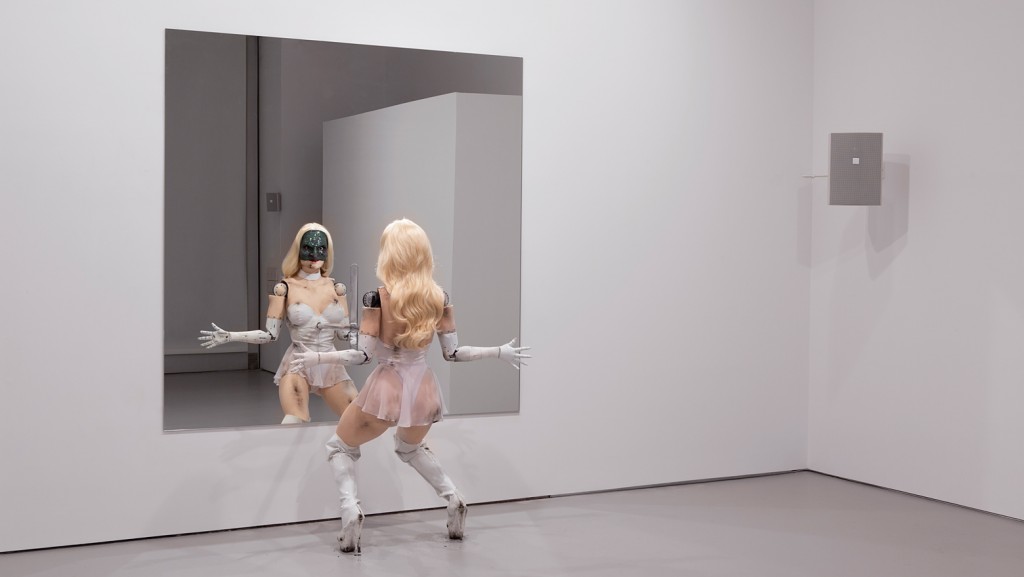

There is nothing more rhetorical than a pose, that decided effort to transcend the contingency of one’s face and posture by means of an eidos, a vehicle whereby the corporeal, the instantaneous, the fungible aspire to the condition of an eternal Platonic idea. In spite of the historical impact of different forms of the anti-portrait (the uncontrollable image of Robert Frank or the zoological passion of Diane Arbus for the singularity of the camera), social habits and professional photographic practice continue to adhere to the pictorial expectation of capturing an idealized “I”: the care lavished on the image and its lighting, the precise coordination of eye and shutter finger, and above all the productive self-censoring of the photographic subject. All these forces conspire to constitute a sublimated emissary that conceals and fabricates, in the face of the camera, a controlled appearance, an artifact of subjectivity. One stops and appears before the camera, one pauses,1 greeting it as a servant approaches his master.

1 The etymology of the word could not be more eloquent. Spanish posar, according to Corominas, derives from Late Latin pausare (‘cease, stop’). In this sense, it shares meaning with the idea of the “presentation” of our ontology. See Joan Corominas, Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana (Madrid: Gredos, 1990), p. 470.

If a pose has a symbolic and culturally constructed quality, a gesture, on the other hand, is an almost organic aspect of our appearance in the presence of others: a clue, no less revealing than the silver bromide of a vintage photograph, of an atomic fact in the endless chain of events that make up the world.

“I believe that there are many societies in Latin America where the task of keeping up the appearances of our family, friends, and group falls to women.”

The transition from analog and chemical photography to the illusionism of digital photography has only radicalized the most ordinary photographic custom: whereas the destruction of a photograph used to entail a certain magical disquiet (ultimately, the cutting or tearing of a snapshot suggested a furious slaughter), the ease of eliminating files from digital devices has empowered photographic subjects to exercise police-state control over the beauty and fitness of their faces.

”We elaborate an image of ourselves that coincides with certain norms in compliance with what everyone else finds acceptable” (Pierre Bourdieu)

“In The Most Beautiful Brides of Baja California (2000-2004) we studied this phenomenon among upper middle class women of Tijuana. Using my friendship to gain access, I found myself researching what people believe being photogenic is all about, and how they choose to present themselves before a photographic camera. In time, I became more interested in seeking out their fragile moments, perhaps those occasions when the subjects were not ready for the photo and were, therefore, unaware of their own representation. My study of this facet proposes to find the human side, based on the construction of a shell that exists in order to be contemplated by others”

Venegas stays away from clear narratives and statements by instead presenting her conclusions to more than four years of work as fragments of an experience, each one a subtle document of a space whose telling reflects on identity.

In her portrayal of wealth and celebrity, Venegas counters expectations on the part of subjects and viewers alike.

Text: Press release, Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Cuauhtémoc Medina for the book Gestus, published by RM editorial in 2015 and Alfonso Morales ‘A factory of dreams’ for the solo exhibition at Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in México City, ‘You will never be younger than this day’, 2012, found on Yvonne Venegas website http://yvonnevenegas.com.

Edit by Magazine Contemporary Culture.

All images belongs to the respective artist and management.