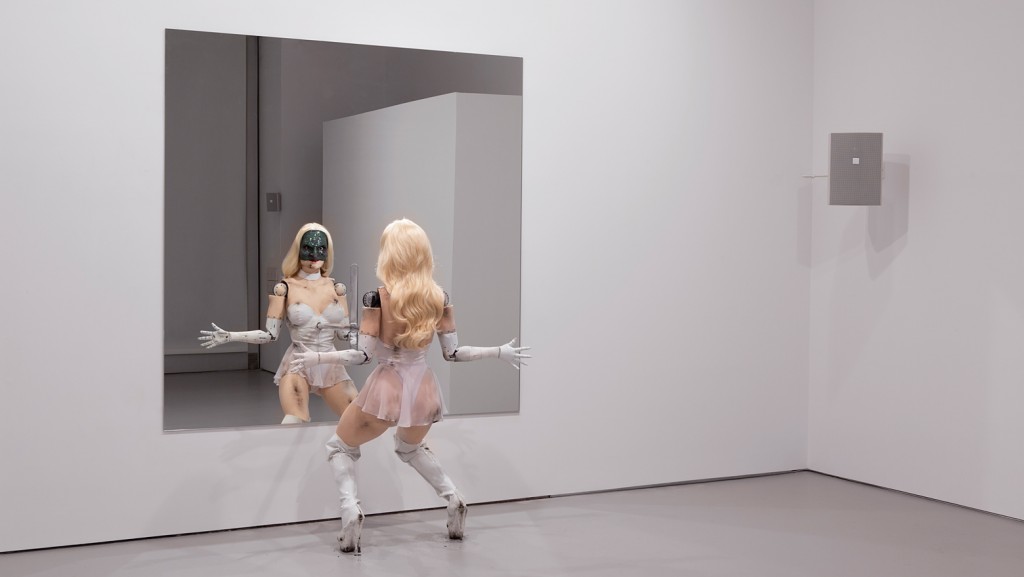

Jordan Wolfs, Female Figure, 2014 and Colored Sculpture, 2016, Installation View

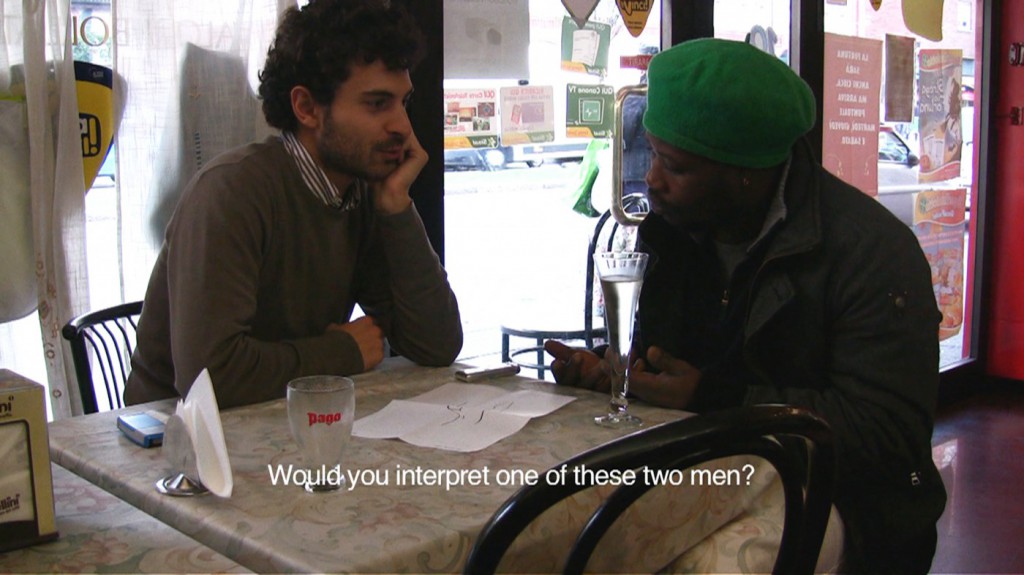

In a recent interview Jordan Wolfson artist traced a cycle of works produced since 2009 back to a moment of eye-contact: “It is something that became clear to me in Your Napoleon (2009) […]. For that work, I kept trying to figure out how to cut and paste these mock conversations about string theory and pop culture, and it felt like an ad-lib […]. I didn’t come up with the term formal bridge until I basically asked the actors to just read the script and look directly into my eyes, stare deep into my eyes” [Jordan Wolfson and Aram Moshayedi, “Tell a Poser,” in Ecce Homo / le Poseur, Walther König, Cologne, 2013, p. 92].If eye contact is both the semblance of a “truthful” connection and in the right hands a mask for falsity, Wolfson has pursued this “formal bridge” into a realm of heightened artifice and discomforting disclosure. His sophisticated animated constructions have achieved an unerring capacity to meld the giddy “anything goes” of computer-generated imagery with the telling fetish of the pop-cultural meme.

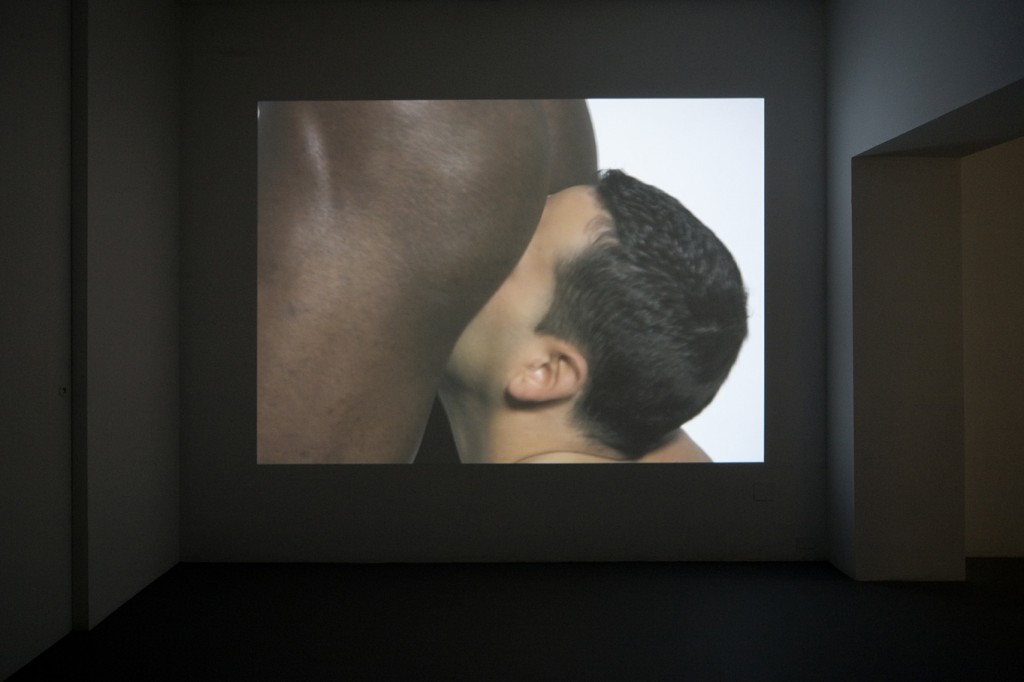

In his first solo exhibition for David Zwirner in New York in 2014, comprising a projected film, an installation and a number of digitally printed reliefs, instances of engineered eye contact between an artwork’s protagonist and the viewer anchored the show. The looped film Raspberry Poser (2012) featured a medley of animated forms layered against stock-image backgrounds and tastefully shot locations, set to a soundtrack of Beyoncé and Mazzy Star. Bouncing HIV virus particles and ethereal floating condoms emitting cascades of love hearts roved the streets and luxury lifestyle boutiques of New York’s SoHo. Meanwhile a generic cartoon boy gleefully strangled and self-eviscerated himself, as if to prove his immortal otherworldliness. Intercut with these characters, a series of live-action sequences showed Wolfson dressed as an archetypal punk on a “dérive” through a Parisian park. A close-up shot sees him turn to the camera and hold the prolonged gaze of the lens, an insouciant smile flickering across his face. The camera, of course, mediates the connection between Wolfson and the viewer. But the intentionality and persistence behind “the look” is unnerving. It holds both an arrogant knowingness and something of the contorted power play of a fashion model’s stare into the camera.

Female Figure 2014 is an almost absurdist endgame for discourse around the theatrics of the sculptural object and the tendency towards stagecraft within the contemporary art exhibition. While the robot’s routine was scripted, programmed and seamlessly looped — not unlike Raspberry Poser playing nearby — the physical nature of the encounter was heightened through the restriction to one or two people entering the room at any time. This conceit, a gesture towards an individualized performance, allowed for the singular experience of being “seen” by “her,” a phenomenon made possible by the use of advanced facial recognition and motion-sensing technology. The robot is the distant figure in the park in Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness (1943). Thought of as a puppet, its relation to the objects around it is purely additive; it creates no new relations in the world of the viewer. In its locking of sight-lines, however, the viewer is momentarily yet disconcertingly aware of becoming an object in the eyes of the automaton.

In many regards, Jordan Wolfson artist work embodies the internalized contradictions of a generation whose teenage years spanned the twin poles of a burgeoning hyper-sexualized cultural economy and the media-stoked specter of sexually transmitted disease. In conjuring up a social imaginary around HIV and AIDS activism, Raspberry Poser echoes a young adult asking: “What does it mean about me?” — what writer Sarah Schulman has described as a “suburban narcissism in which one is able to ‘identify’ in order to internalize value”[Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, University of California Press, Oakland CA, 2012, p. 7]. The “place of distortion” Wolfson moves toward is undoubtedly agonistic, as it rests on a neurotic self-identification that appropriates positions of sexuality, gender, race and class — positions that themselves are present in the work only through inflated, vulgarized stereotypes. “Do you think I’m homosexual? Do you think I’m rich? Will you tell them what it’s like to be with me?” The artist’s needy voice is caught within the performance of a hyperbolized role, a meta-dialogue with the viewer that challenges their presumptions of identity and the “honest” disclosure of inner angst. While Wolfson is evidently not himself the loose-skinned, tired man of the poetic monologue in Female Figure 2014, the psycho-sexual inner world of the creator of the Bellmer-esque robot-as-sex-object looms large as an involuntary fiction.

There is a clear sense in which the artist’s work from 2009 onward has rejected a reliance on acquired methods and signifiers of artistic validity and rectitude. The complex cycle of works that culminates in the twin gazes of the female automaton and the languid punk instead offers witness to an unadorned self-image at odds with the governing techniques of the self-enterprising individual. Wolfson’s adoption of animation and animatronics locates this externalization within structural ambivalence; the ability to warp, inflate, distort and fantasize offers a fitting testimony to the splitting of contemporary subjecthood.

Source: Kunstforum International, June July 2016 Issue.

Text: Richard Birkett, Flashartonline.com.

All images belongs to the respective artist and management.